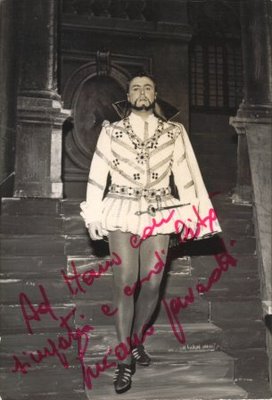

Another great one passes

Of course the title of this entry speaks of the most famous singer of all to have died in recent months.

Of course the title of this entry speaks of the most famous singer of all to have died in recent months.There are very few singers about whom I have as much ambivalence as I do Pavarotti. But that is because I abhor the commercialization of our art. I prefer to live in that rarefied sphere where money and commerce never appear. (That was not intended to be a rhyme!)

And yet Pavarotti turned opera (or "opera", if you will) into a stadium event. His handkerchief and enormous personality invaded more homes than any other singer's in recent memory. Did he turn more people on to opera, or did he simply coarsen and cheapen the taste of the general public so they believed that three tenors screeching "vincerò" in quasi-unison was what Opera all about? Was it his commercialization and commodification of our profession that opened the door for such abominations as Andrea Bocelli, Charlotte Church, Russell Watson and Katherine Jenkins? (And on that subject, I don't care if Gergiev and Abbado conduct recordings by Bocelli, that does not alchemize him into a singer.)

But you see, this is the problem with Pavarotti: that we forget (or perhaps it is only I who forget) that in his early years, he was a truly great singer. He was called the King of the High C's for a reason. Yes, it was pure hype dreamed up by Herbert Breslin or Decca's publicity hounds (or whomever) but neither Domingo or Carreras were ever in any danger of being touted for their exceptional high notes.

No, Pavarotti at his best was a superhumanly gifted singer. He was also a showman who knew how to kowtow to an audience and to appeal to the lowest common denominator. But just for once, especially on the occasion of his demise, can I not simply look the other way, or turn my ear the other way and just exult in the sheer brilliance of his singing.

He was an astute technician. One had only to watch him sing to realize the profound concentration at work whenever he opened his mouth (to sing, at least, if not always to talk).

He did not have the most beautiful tenor voice per se. To my ear the basic sound was rather resiny and the legato became gummier the heavier the repertoire he assumed. (Otello, Ernani? PLEASE!) But when he was singing the repertoire he was intended by nature to sing (Rodolfo, Tonio, Edgardo, the Duke, Riccardo, Nemorino [though here his 'ingratiating' personality really grated on me]) he was matchless. Certainly among singers in his generation he was possessed of a unique technical aplomb, acuity and self-awareness. Even when he moved beyond the completely healthy spectrum of roles and began singing Cavaradossi and Calaf, he managed by virtue of his technical grounding to convey a reasonable facsimile of those roles.

He did not have the most beautiful tenor voice per se. To my ear the basic sound was rather resiny and the legato became gummier the heavier the repertoire he assumed. (Otello, Ernani? PLEASE!) But when he was singing the repertoire he was intended by nature to sing (Rodolfo, Tonio, Edgardo, the Duke, Riccardo, Nemorino [though here his 'ingratiating' personality really grated on me]) he was matchless. Certainly among singers in his generation he was possessed of a unique technical aplomb, acuity and self-awareness. Even when he moved beyond the completely healthy spectrum of roles and began singing Cavaradossi and Calaf, he managed by virtue of his technical grounding to convey a reasonable facsimile of those roles.I have two reminiscences of Pavarotti. The first was the single time I heard him sing live. Ballo in Chicago. It was Scotto I went to hear; it was mere chance that he was singing Riccardo. These were the last performances that Scotto and Pavarotti were to give together. Earlier that season, in Gioconda in San Francisco, each singer was assuming their part for the first time ever. I don't remember the particulars, but somehow Pavarotti upstaged Scotto in the final curtain call or some such, and she was captured on camera having a hissy diva fit to end all hissy diva fits. She swore that, after the already-scheduled Ballo in Chicago, that their paths would never cross again. (You know, those Italians and Greeks [you know who you are]: they're so hot-blooded and grudge-holding. You cross them once and you cease to exist.) So in the second act love duet, their supposed ardor looked much more like repugnance. I will never forget the way that Scotto, singing the words, "Ebben, sì, t'amo" [All right, I confess it: I love you] looked away from him as from a particularly unsavory odor.

Another time, numerous years later, by a chance set of happy accidents, I was in Busseto, Italy, my first time abroad, playing for Carlo Bergonzi's master class at the so-called Bel Canto Institute. Some day I will have more to say about that experience. For the time being, it was, in a word, extraordinary.) One day at lunch (this event took place in Bergonzi's hotel I due Foscari, where three times a day we were fed the most magnificent food), there were excited whispers that Pavarotti was going to be stopping by that afternoon. Sure enough, shortly before the obligatory afternoon siesta, the great man showed up, his current squeeze (Madelyn Renée: anybody remember her?) in tow. He did not stay long, merely looked genial, paid his respects to Bergonzi and Maestro Mantovani, an elderly master teacher who had worked at La Scala and with Pavarotti, and who was working with students, said a few encouraging words to the students and left. Even in those few moments, even to someone who was not at all kindly disposed toward him (how could he have treated poor Renatina so badly?), the sheer charismatic force of his personality swept all before it. It was not so much that he was large of figure (though of course he was), but that he exuded a magnetism that beguiled as it blinded.

I do have a number of Pavarotti recordings, though again, his presence on them is mostly coincidental (I have pirates of the Scala Kleiber-led Bohème with Cotrubaş, the Met Bohème with Scotto that was the first Live from the Met telecast, the infamous San Francisco Gioconda with Scotto, as well as their valedictory joint appearance in the Chicago Ballo, in addition to some of his choicest studio recordings).

I have had much occasion these past few months to memorialize those supreme artists who have gone on to their greater reward. In many cases, I found myself with new-found (or newly-rediscovered) appreciation for what made them special.

The same is true here. Please listen to this live recording of O soave fanciulla featuring the young Mirella Freni to hear what I mean. Apart from the nearly flawless technique, there is a clearly-perceivable interplay between him and the gorgeous Mirella.

This is how he should be remembered, and how I want to remember him. Let us send him out in style. And with a huge debt of thanks for having at times transcended his own commercialism to give us what we really needed. And what he really needed: the adulation of his public.

Labels: andrea bocelli, boheme, luciano pavarotti, mirella freni, renata scotto, three tenors